The Short and Long-Term Neutral Rate

Re-hashing some old concepts

With the heightened speculation running into Jackson Hole and Powell’s Friday speech, it is important to take a holistic view. In a speech in 2018, Governor Brainard gave a great glimpse into how the FOMC looks at both a short and long-term neutral rate when assessing future monetary policy actions. You can find the speech here. She is no longer part of the committee but acted as vice chair until February this year. She is now the director of the National Economic Council.

Remember that back in September 2018, the Fed had hiked from 0.25% in late 2016 to 1.75% when Brainard delivered her speech (and had another 50bp to go before reaching the terminal rate for that cycle). In her remarks, she made the distinction between short and long-run neutral rates.

Here are the descriptions she uses for each:

The "shorter-run" neutral rate does not stay fixed but rather fluctuates along with important changes in economic conditions. For instance, legislation that increases the budget deficit through tax cuts and spending increases can be expected to generate tailwinds to domestic demand and thus push up the shorter-run neutral interest rate. Heightened risk appetite among investors similarly can be expected to push up the shorter-run neutral rate.

The underlying concept of the "longer run" generally refers to the output growing at its longer-run trend after transitory forces reflecting headwinds or tailwinds have played out in an environment of full employment and inflation running at the FOMC objective.

Back then, her takeaway was that short-term neutral was likely above long-term, and hence, she advocated for further tightening. Looking at the chart below (blue line long-term Fed Rate, red actual Fed Funds), they were never able to push the short-run rate above their long-term rate projections.

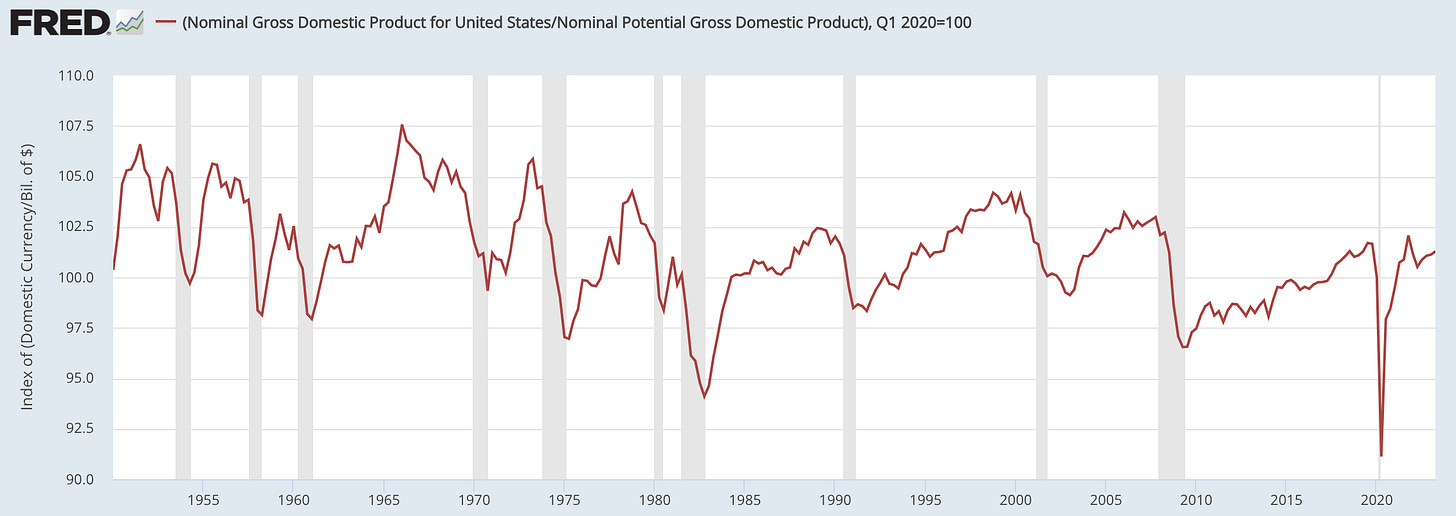

The current Fed is doing exactly the same thing. Current Fed Funds are well above the 2.5-3.0% estimate of long-term neutral. To cause the long-term neutral rate to rise, there would need to be a lengthy period of positive output gap. It’s hard to see that in current economic data. Inflation is running higher, but not because of widespread excess demand and/or a catastrophic decline in potential output. US potential GDP remains, as it was, around 2%. The below chart shows the output gap as a simple ratio of potential NGDP / GDP.

Taking it all in would suggest a way too premature talk about any need for longer-term neutral rates to rise. It is possible, but given their dismal forecasting performance, how would the Fed be so sure of such an outcome? The higher R* folks will be disappointed. Higher short-run neutral might still be some way off, so any hints towards such a possibility would obviously hit the front end hardest. Either way, I personally think it will be a non-event relative to current narratives.

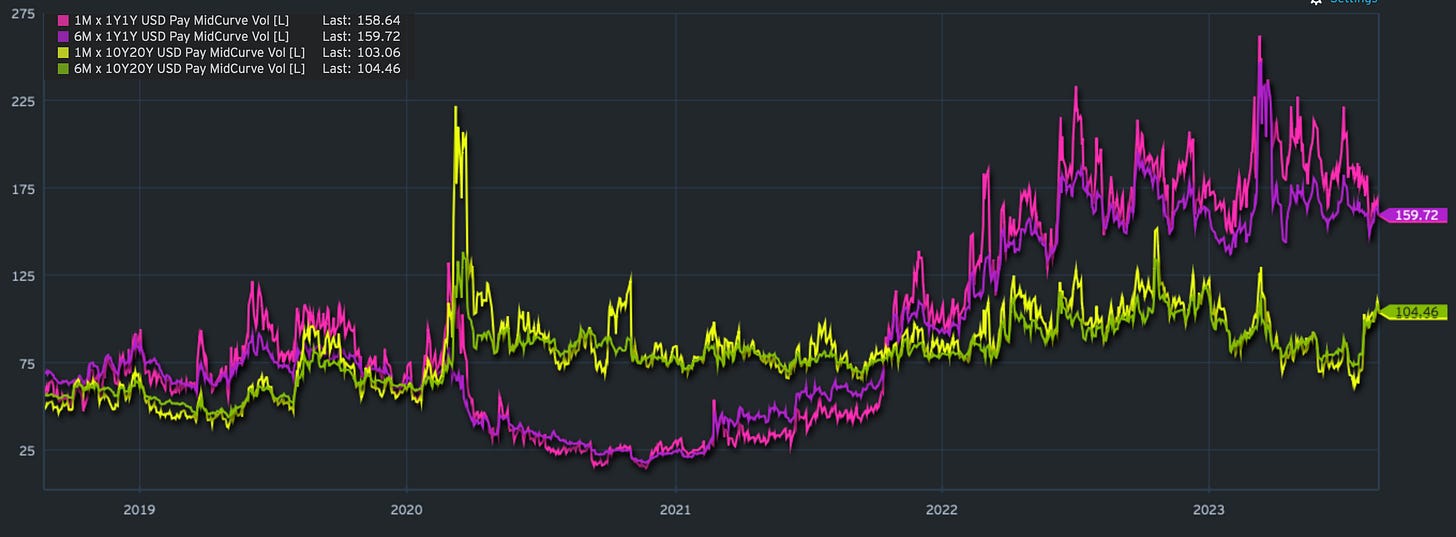

Looking at mid-curve options (1-month and 6-month options on forward starting swaps) would indicate a pop in longer-dated forward 10y20y relative to 1y1y forward volatility. Overall, however, this is within a well-defined range over the past few years.

Good Luck out there!